This example Asia Pacific Region Politics And Society Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

Scholars have recognized that, despite free elections, leaders in new democracies may not be accountable to their citizens. One reason for this is that the state apparatus is difficult to control. Authoritarian rulers use bureaucracies to pursue their objectives. In doing so they create complex institutional structures that are not necessarily brought to heel once elections occur and new governments are in place. The transition to democracy thus also involves a complex struggle over controlling the state apparatus and thereby enhancing accountability.

In posttransition Asia, politicians have chosen to pursue two primary types of proaccountability mechanisms, or reform paths: formalized/institutional and informal/social. The institutional mechanisms include laws such as Administrative Procedure Acts (APAs) that constrain the bureaucracy with various requirements when making policy, legislative oversight, and judiciaries. The social, societal, or informational mechanisms, in turn, include independent agencies, civil society organizations, and the media.

At their core, each of these mechanisms is about sanctions. National legislatures in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, for example, have passed APAs to open up central bureaucracies and their policy-making processes by legalizing and formalizing accountability measures. In each case, in addition to APAs, the judiciary also plays a crucial role, as politicians can decentralize monitoring of the bureaucracy by using judicial review of administrative actions (i.e., giving citizens the right to sue).

Another path that governments can take is increasing citizen participation through informal or social accountability mechanisms, through which citizens function as watchdogs, impose sanctions, and can even activate institutionalized punishment mechanisms. Interestingly, international organizations (IOs) such as the World Bank or foreign aid agencies such as U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have often supported such measures, which coincide with general decentralization efforts.

This entry presents the different ways that politicians try to restructure the state with the aim of increasing accountability. First the range of major mechanisms of control available to politicians, as discussed in the literature, is reviewed. Next comes discussion of the trends in their use in Asia during the past two decades. Then the disparate research programs that constitute the literature on state accountability and democratization are synthesized into a more coherent framework. The goal is to clarify the relationships between the actors and link them to the types of control mechanisms chosen to increase accountability.

The Asian Experience

Given the two main types of proaccountability measures— formalized/institutional and informal/social—where does Asia fit in? Asia is a fruitful region to study questions of accountability because the region includes states f acing common problems unfolding within differing political institutional contexts. South Korea, for instance, had a large developmental state that had supported the maturation of the private sector, but at the expense of other concerns. Taiwan was similar to South Korea but with policies favoring a particular partisan constituent: the Kuomintang (KMT, the dominant party in Taiwan for fifty years until recently). The Philippines is somewhat different from either of these countries; even though its bureaucracy had been a source of patronage prior to transition, the executives continue to rely on it as a means of controlling their agents post transition. What these three countries share in common is that leaders following democratic transitions faced a governance dilemma: how to rein in a central bureaucracy that had long favored a restricted set of interests? In all these cases, and as one can imagine in many other post transition states, politicians face a similar problem of reorienting an entrenched bureaucracy. Thus, holding free and fair elections, while critical, only addresses the representation aspect of democracy but not necessarily the responsiveness aspect. After all, central bureaucracies are responsible for implementing laws that elected members of the legislature pass.

From the recent experiences of states in Asia, it is apparent that some states have more options than others. The choice of which reform path to follow appears to rest on two factors: capacity and institutional openness. Tom Ginsburg (2001) observes that states with significant preexisting bureaucratic capacity, such as Japan and Korea, face a choice concerning the degree to which they want to open the bureaucracy. States without strong bureaucratic systems—that is, those lacking high-capacity bureaucracies—seem to have opted for decentralization. This option appears especially popular in assuaging fears of corruption and carryover from autocratic regimes, because it physically moves the location of much of the bureaucratic interaction. Additionally, states pursuing decentralization are able to exploit international organization involvement— especially the World Bank—to help with decentralization and increasing social accountability.

The key cases of formal or institutional adopters are Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. South Korea and Taiwan opened up their bureaucracies significantly, while Japan did so more modestly as a result of institutional constraints. The political tradeoff that these three states faced between more or less openness in an APA or Administrative Procedure Law (APL) is very different from the challenges facing newly democratizing states such as the Indonesia and the Philippines. These states are more concerned with general governance issues. In cases like these, note Jose Edgardo Campos and Joel Hellman (2005), “the decision to decentralize is sparked by strong reactions to a prolonged period of highly authoritarian rule” (238).

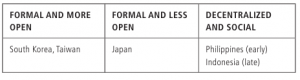

But what specific measures have states adopted? Table 1 summarizes the key example countries for each of the major categories. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan represent cases of formal, institutionalized accountability measures (or “vertical” accountability). South Korea and Taiwan have formally opened their bureaucracies much more extensively than Japan, which has used the APL primarily to delegate some monitoring functions to the courts. Indonesia and the Philippines have both followed a path of decentralization and increasing social accountability measures, largely with the aid of the World Bank. The Philippines is further down this path, given the length of time since transition, but Indonesia appears to be following suit.

It should be noted that in none of these cases are such measures fully effective at preventing politicians or bureaucrats from evading their intent. Perhaps it is inevitable that these measures will never live up to their full potential, but the amount of slack given and accepted is nonetheless noteworthy.

Mini Country Reviews

The remainder of this entry briefly looks at the various mechanisms used in posttransition Asia to increase accountability. As noted, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are the three best examples of heavily institutionalized mechanisms of control, whereas Indonesia and the Philippines, as well as India, to some extent, have followed a more decentralized, social accountability route, often with the help of organizations such as the World Bank. That said, it is important to bear in mind that even with laws on the books, some scholars remain skeptical about full implementation or full closure in all of these countries.

The Philippines

The Philippines is a good example of the range and variety of measures leaders may undertake. The overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986 led to a major push for decentralization of Filipino politics. In 1991, the state undertook massive decentralization aimed at moving government downward—to create “responsive and accountable local governance structures.” The government was not only responding to internal pressures for decentralization. The USAID also was pushing for decentralization in the Philippines, arguing that movement toward the local level is good for democracy. The World Bank also has been involved in supporting the use of the Citizen Report Card, as well as in promoting interaction and aid at the local level. It has identified local capacity building and performance monitoring as two areas of priority for its work at the local level.

Table 1: Major examples of types of accountability measures in Asia

In addition to these shifts, the Filipino government has implemented informal/social accountability mechanisms at all levels. Ombudsmen were introduced in 1994 and now exist at every level of local government. The key document in the Philippines is the Local Government Code of 1991.The intent of this document was to “break the self-perpetuating nature of centralized power” particularly after Marcos, notes Malcolm Russell-Einhorn (2007). Key formal accountability measures now include “right to information” provisions, rights of initiative and referendum, public hearings for key decisions, establishment of village development councils, and the right to petition to prioritize debate of legislation.

Despite sweeping reforms—both formal and informal attempts to increase the informational mechanisms—follow-through has been incomplete. The statute is vague about how public hearings should be conducted and contains no provisions for notice of hearings. Local governments are not required to release information.

In fact, many APAs fail to specify public notice and comment requirements. Russell-Einhorn (2007) writes that there are “local special bodies that serve as critical advisory groups on particular issues, including those dealing with health, public safety, education, infrastructure procurement, or local development. . . . These groups can propose, not approve or monitor initiatives or compel information” (217).

That said, it is noteworthy that some scholars see “bureaucratic tradition” as limiting accountability throughout the region (including in Thailand and Indonesia). Like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, opening up the bureaucracy—particularly after a nondemocratic regime shored it up—is one of the key challenges in creating long-term accountability in many of new democracies, including the Philippines.

Indonesia

Indonesia has followed a similar, if more gradual, path as the Philippines. Emerging from authoritarian rule, it has sought to increase accountability by decentralizing. “Big Bang” decentralization began in 2001. This first round of decentralization included shifting control over civil servants to the local rather than central government. The World Bank has had a strong role in these efforts, particularly in promoting local and district involvement. For example, the World Bank is exploring a Justice for the Poor initiative, which is a decentralized, community participation approach, according to John Ackerman (2005, 44).

Formal administrative procedures reform also has made headway recently in Indonesia. In April 2008, an expanded Freedom of Information Act passed and will be fully implemented by 2010.This law requires that bureaucratic institutions make at least biannual public updates and promptly disseminate information relating to public order or services. The World Bank lobbied for this bill along with Indonesian civil society organizations.

Other measures of note include anticorruption laws that, since 1998, have provided access to information and freedom of the press. As with the Philippines, there are active advocacy campaigns supported by IOs, but they are not yet as well developed, given the relatively short time since transition.

Thailand

Like many other states in Southeast Asia, Thailand had a long history of military y author Italianism. Observers saw the 1997 constitution as a chance to implement progressive reforms. Civil society groups played a role in drafting it, and accordingly constitutional provisions included seven new proaccountability institutions. These include creation of a National Counter Corruption Commission, independent electoral commission, ombudsman, constitutional court, administrative court, environmental review board, and consumer review board. Formal accountability measures include “right to information” provisions—sections 58 and 59 of the 1997 constitution.

In addition to the 1997 changes, a Thai decentralization law passed in 1999. Although the government has been slow to implement this law, it formally calls for local collection of taxes, a major new provision. There are also questions about the potential vague or contradictory provisions of such local government laws, further hindering effective decentralized governance and accountability. While the hallmarks of the decentralized, social, and informational accountability oriented reform path are present in Thailand, as in the Philippines and Indonesia, bureaucratic traditions have proved difficult to break.

India

Like the Philippines, India’s accountability measures have been largely of the social and informational variety. Formal accountability measures include “right to information” provisions. Additionally, the Indian government has implemented accountability measures in a highly decentralized way. In 1992 and 1993, the Indian constitution was amended to create more levels of government, including at the federal, state, and municipal levels. Civil society groups have used this massive decentralization to bring government, as well as accountability measures, closer to the people.

This said, there has been a major push within India to promote local and community involvement in policy as well as to work with nongovernmental organizations at those levels. Additionally, India is experimenting in some cities with using a World Bank Citizen Report Card. The initial city-level experiment involved Bangalore in 1994. Other accountability measures vary by state or even municipality. For example, Kerala has a program designed to empower local councils, based on highly participatory village-based planning, while Goa has adopted a much more liberal Right to Information Act.

Japan

Japan’s accountability measures have been largely formal in nature. Japan recodified its APL in 1995 and 1997. This set up an Administrative Appeals Commission under the prime minister to handle nonjudicial appeals. These courts can revoke or alter administrative depositions but have rarely done so in practice. While a Japanese Freedom of Information Act exists, it has many loopholes and has thus proved largely “toothless,” observes Ginsburg (2002, 253–254).

The Japanese case represents a very formalized system, but one that is used only at the behest of a strong ruling party. The dominance of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has provided little incentive to open up the policy-making process through open provisions as seen in the South Korean case or other, more decentralized regimes. Ginsburg (2001) finds that the Japanese bureaucracy after the APL has kept the policymaking process relatively closed but has lightened monitoring and control mechanisms by involving the courts more extensively. However, it appears that the courts see only the cases that are relatively less important to politicians.

IO involvement in Japan is relatively limited in relation to its more decentralized neighbors (there are ant bribery reports issued on Japan and South Korea by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). This institutional reality—centralized LDP dominance—makes Japan a special case of formal accountability measures, in which politicians with unusually long time horizons do not see any advantage to opening up the bureaucracy or even to protecting themselves in times when they are out of office.

South Korea

Opening up South Korean bureaucracy and increasing accountability have followed a similar path as in Japan. Ginsburg (2001) notes that these reforms are seen partly as resulting from Japanese influence in general, and its recently adopted APL in particular, but also as a result of democratization and a desire for the bureaucracy to be more responsive to a broader set of interests. Specifically, in transitions in which the executive’s preferences are aligned with the status quo elements in the bureaucracy—as in South Korea and Taiwan initially—governments prefer continuity in structure and process and so opt for strengthening or maintaining executive control. But where the government is facing a bureaucracy with divergent preferences and has legislative support for reform, it chooses to attack these entrenched interests and achieve greater accountability with control mechanisms such as an APA. Unlike countries such as the Philippines and Thailand, South Korean reforms are primarily highly institutionalized, rather than being oriented toward decentralization and social accountability.

The core reform law was the 1994 APA (amended in 1997) that restricted the bureaucracy’s discretion over the policy-making process. Administrative reform had been in the works for almost a decade, following a failed 1987 attempt at an APL. In 1994, South Korea passed a law creating an administrative appeals court. Then, in 1995, a reform to the 1994 law referred to the court all appeals against the government and empowered it to “revoke or alter administrative dispositions as necessary” (Administrative Appeals Act, Article 6–2, in Ginsburg, 2001, 606).

The South Korean APA requires advance public notice and comment, which opens up the policy process to those interests that have not been previously aligned with the ruling party. The 1996 Disclosure of Information Held by Public Authorities law, which is subject to judicial review, significantly opens up policy making. Through these and other related reforms, the South Korean bureaucracy and policy process have grown much more open and are subject to greater oversight by a wider range of actors, including courts and independent actors such as ombudsmen.

Taiwan

Like South Korea, Taiwan’s reforms have focused on formalizing institutional structures and processes for increasing accountability. Administrative reforms were driven by the need for the ruling party (the KMT) to change its image from one of entrenched corruption and favoritism toward wealthy private interests to one of “clean government.” To do so, the party had to rein in the very bureaucracy that had long served as the cornerstone of its power.

Taiwan’s 1999 APA requires public notice and comment of all proposed regulations and that agencies investigate administrative action appeals and notify all relevant parties of their decisions. A Freedom of Information provision is another major feature of Taiwan’s APA. This requires that most agencies disclose information to the public upon request. The APA also allows formal adjudication, whereby parties have the right to present evidence and cross-examine witnesses at an oral hearing. Additionally, the 1994 amendments to the Administrative Litigation Law established an administrative court. Taiwan’s 1998 Administrative Litigation Act, in turn, allows judicial review of administrative actions.

Conclusion

There seem to be two primary paths for increasing accountability in the Asian experience during the past twenty years. One path—followed by Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—is highly institutionalized, although there is significant variation between these three cases. The Japanese bureaucracy is still relatively insulated compared with South Korea and Taiwan, but these three countries nonetheless contrast sharply with the more decentralized systems of Indonesia and the Philippines. IOs, particularly the World Bank, appear much more willing and able to assist with these more decentralized paths.

The literature has tended to focus on one or the other path and variation within that path. Thus far largely unexplored are the equally important questions of why these appear to be substitutes and the conditions under which states select a particular set of tools. Are decentralization and social accountability chosen only out of necessity? Alternatively, if this proves to be a more common path outside of Asia, the question arises as to whether a “Japan” would ever choose such a path, and if so when? Is social accountability really a second choice, behind the more preferred alternative of an APA? Or is it more likely that these states prefer to pursue these types of “good governance” building measures and in doing so sometimes conclude that IO assistance (particularly World Bank) will ease some of their burden? Determining the circumstances under which states will opt for administrative reform, the path they will follow if they do pursue such reforms, and the particular tools they will select under different conditions all represent potentially fruitful avenues for future research.

To some extent, time will tell about the progression of the decentralized cases. Accountability along the decentralization path appears to hinge on two factors: the effectiveness of decentralization and the strength of civil society groups, including those with IO assistance. Presumably increases in both of these should aid accountability, but in some countries this seems like a lot on which to hang one’s hat.

Bibliography:

- Ackerman, John M. “Social Accountability for the Public Sector: A Conceptual Discussion.” In Social Development Paper 82. Washington, D.C.:World Bank, 2005.

- Baum, Jeeyang Rhee. “Presidents Have Problems Too:The Logic of Intrabranch Delegation in East Asia.” British Journal of Political Science 37, no. 4 (2007): 659–684.

- Baum, Jeeyang Rhee. Responsive Democracy: Increasing State Accountability in East Asia. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming. Bennett, Colin J. “Understanding Ripple Effects:The Cross-national Adoption of Policy Instruments for Bureaucratic Accountability.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 10, no. 3 (1997): 213–233.

- Campos, Jose Edgardo, and Joel S. Hellman. “Governance Gone Local: Does Decentralization Improve Accountability.” In East Asia Decentralizes: Making Local Government Work, 237–252. Washington, D.C.:World Bank, 2005.

- Geddes, Barbara. Politician’s Dilemma: Building State Capacity in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Ginsburg,Tom. “Dismantling the ‘Developmental State’? Administrative Procedure Reform in Japan and Korea.” American Journal of Comparative Law 49, no. 4 (2001): 585–625.

- “Comparative Administrative Procedure: Evidence from Northeast Asia.” Constitutional Political Economy 13, no. 3 (2002): 247–264.

- Goetz, Anne Marie, and John Gaventa. “Bringing Citizen Voice and Client Focus into Service Delivery.”Working Paper 138. Brighton, U.K.: Institute of Development Studies, 2001.

- Iszatt, Nina T. “Legislating for Citizens’ Participation in the Philippines.” LogoLink Report. Brighton, U.K.: Institute of Development Studies, July 2002.

- Kaufmann, Daniel. “Myths and Realities of Governance and Corruption.” In Global Competitiveness Report 2005–2006, 81–98.Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2005.

- McGee, Rosemary. “Legal Frameworks for Citizen Participation: Synthesis Report.” LogoLink Report. Brighton, U.K.: Institute of Development Studies, 2003.

- Moreno, Erica, Brian F. Crisp, and Matthew Shugart. “The Accountability Deficit in Latin America.” In Democratic Accountability in Latin America, edited by Scott Mainwaring and Christopher Welna, 79–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- O’Donnell, G. “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies.” In The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies, edited by Andreas Schedler, Larry Diamond, and Marc F. Plattner, 29–52. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1999.

- “Horizontal Accountability:The Legal Institutionalization of Mistrust.” In Democratic Accountability in Latin America, edited by Scott Mainwaring and Christopher Welna, 34–54. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Russell-Einhorn, Malcolm. “Legal and Institutional Frameworks Supporting Budgeting and Accountability in Service Delivery Performance.” In Performance Accountability and Combating Corruption, edited by Anwar Shah, 183–232.Washington, D.C.:World Bank, 2007.

- Smulovitz, Catalina, and Enrique Peruzzotti. “Societal and Horizontal Controls:Two Cases of a Fruitful Relationship.” In Democratic Accountability in Latin America, edited by Scott Mainwaring and Christopher Welna, 309–331. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Stokes, Susan. Mandates and Democracy: Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- “Perverse Accountability: A Formal Model of Machine Politics with Evidence from Argentina.” American Political Science Review 99, no. 3 (2005): 315–325.

- Wolfe, Robert. “Regulatory Transparency, Developing Countries, and the Fate of the WTO.” Paper presented at the meeting of the International Studies Association, Portland, Ore., March 2003.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples