This example United Nations Climate Change Conferences Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

The involvement of the United Nations in the issue of climate change began through its specialized agency, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) that, in 1969, called for a global network for monitoring pollutants suspected of contributing to climate change. Increasing international scientific attention to climate change and severe, decadal drought in the Sahel region of Africa led the WMO to convene the First World Climate Conference in 1979. The conference statement called for international cooperation to advance understanding of climate and climate change and established the World Climate Program to collect data and coordinate climate change research at the domestic level. This served as an impetus for a number of countries to develop national climate research programs.

Growing Momentum In 1980s

There were a number of smaller international meetings in the 1980s, the most important of which was held in Villach, Austria, in 1985. Sponsored by the WMO, United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), and the International Council of Scientific Unions, the conference is seen as a major turning point in climate change science and policy as it provided international scientific consensus as to the magnitude of the issue, potential social and economic consequences, and urged states to take action to develop policy recommendations to mitigate climate change.

A group of scientists emerging from the Villach conference became active in developing a science and policy network that was instrumental in organizing the 1988 World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere in Toronto, sponsored by the Government of Canada, WMO, and UNEP. The Toronto conference was the first with an explicit political dimension and a strong conference declaration; this included a proposal that governments cut the 1988 level of carbon dioxide emissions by 20 percent by 2005, and that eventually emissions would need to be stabilized at 50 percent of existing levels.

What is notable about these first climate conferences is that they were by invitation only and were predominantly attended by scientists. The attendees were not official delegates of their respective countries and the conference statements, while calls to action, were neither negotiated nor agreed to by the participants’ home states, nor were they binding. Nevertheless, the Toronto recommendations are cited as the basis for Germany’s 25 to 30 percent carbon dioxide reduction goal affirmed in 1990, a key factor in generating concern for climate change in Canada, and triggered congressional action in the United States.

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change

Recognizing the need for climate change policies and recommendations to go through diplomatic processes, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was formed through a United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution after the Toronto Conference in 1988. Its goals were to organize scientific information, evaluate risk from climate change, and consider mitigation strategies to inform treaty negotiations in establishing a convention on climate change. Governments had much greater control over the IPCC, as they selected experts and placed high-ranking foreign ministry officials in key positions.

Subsequent to the release of the first IPCC report, the Second World Conference on Climate Change was held in 1990. This meeting had both scientific and diplomatic components, with declarations reflecting the two groups’ positions. The scientific, or technical, declaration was a strong call for action. While the ministerial declaration advocated action, it did not set time frames as more formal treaty negotiating process had been scheduled by the time the conference was held. In December 1990, the UNGA established the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to negotiate the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).The convention was opened for signature at the Rio United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development Earth Summit in June 1992, where it received 155 signatures.

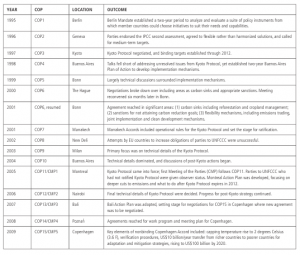

Table 3: Major United Nations Climate Change Conferences, 1995 To 2009

Conferences Of The Parties

Since coming into force, the parties to the UNFCCC have met annually at the Conference of the Parties (COP) to negotiate binding commitments, assess progress, and establish principles and mechanisms for addressing climate change (see Table 1). The relative success and impacts of these meetings have varied substantially over time. The outcome of third conference (COP3), the Kyoto Protocol, was perhaps the most significant as it established binding targets through 2012 to Annex 1 (industrialized) countries. However, the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, the United States, failed to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, and it did not include commitments for major developing countries such as China and India.

With the Kyoto Protocol nearing expiration, the stage was set for a new round of negotiations at Copenhagen in 2009. The Copenhagen Accord fell short of expectations with a nonbinding agreement lacking firm targets for reductions in greenhouse gases. The accord was negotiated by the United States, Brazil, South Africa, India, and China on the final day of the conference and was “taken note of,” not “adopted,” by the parties to the UNFCCC. Blame for the failure of the negotiations has been attributed to the United States for continuing its stance of not agreeing to binding targets, to China and India for frustrating the process so as to not thwart economic growth, and to the nontransparent process that took place among a limited number of countries in drafting the accord.

Bibliography:

- Aldy, J. E., and R. N. Stavins, eds. Architectures for Agreement: Addressing Global Climate Change in the Post-Kyoto World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Jäger, J. “From Conference to Conference.” Climatic Change 20, no. 2 (1992): iii-vii. Ministry of Climate and Energy of Denmark. “COP1-COP14.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. www.en.cop15.dk/climate+facts/process/ cop1+–+cop14.

- Paterson, M. Global Warming and Global Politics. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Social Learning Group. Learning to Manage Global Environmental Risks.Vol. 1, A Comparative History of Social Responses to Climate Change, Ozone Depletion, and Acid Rain. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2001.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). “Decisions of the COP and the COP/CMP.” UNFCCC Secretariat. www.unfccc.int/documentation/decisions/items/3597.php.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples