This example Cabinets And Cabinet Formation Essay is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need a custom essay or research paper on this topic please use our writing services. EssayEmpire.com offers reliable custom essay writing services that can help you to receive high grades and impress your professors with the quality of each essay or research paper you hand in.

The British essayist Walter Bagehot, in The English Constitution, famously defined the cabinet as a “combining committee—a hyphen which joins, a buckle which fastens the legislative part of the State to the executive part of the State” (Bagehot, 1867, 68). As such, the concept does not travel far outside parliamentary systems of government, but one needs to amend it only slightly to give it wider applicability: It is the most senior constitutional body, politically responsible (to parliament or president or both, depending on the political system) for directing the state bureaucracy. The cabinet is part of the broader concept of the government; not all (junior) ministers are cabinet ministers. In the United Kingdom, for example, of over one hundred ministers, only about a quarter are in the cabinet.

Cabinet Structure

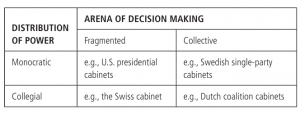

With regard to the cabinet function, the constitutional conventions are for it to deliberate collectively and for each cabinet minister’s voice to count equally. Together, collective decision making and ministerial collegiality form an ideal type of cabinet government, with existing cabinets often deviating from one or both of these norms. Both collectiveness (the arena of decision making) and collegiality (the distribution of power) are dimensions of the cabinet’s structure.

Dutch coalition cabinets, for example, are still close to the ideal type, with a cabinet that meets at least weekly for several hours, during which proposals are actually debated and sometimes amended, and with a prime minister whose formal powers are constrained by being the leader of only one of the political parties in the governing coalition. In the United States, the experience is completely different in both respects: although there is a “Cabinet Room” in the White House, and most newly elected presidents promise to use it, the president primarily deals with individual department secretaries bilaterally, and the cabinet as such rarely meets to deliberate on government policy. In addition, since the president is not only the chair of this cabinet but also the person to whom secretaries answer, the president holds a very powerful position. In this way, the U.S. cabinet is probably closest to the seventeenth century origins of the cabinet as a set of individual advisers to the (British) monarch. That collectiveness and collegiality are linked in the two examples above does not mean that the two dimensions can be collapsed. A prime minister can be dominant but exercise powers within meetings of the full cabinet (as is the case in Swedish single-party cabinets); or the prime minister can really be simply “a first among equals” without the cabinet serving as the principal venue for deliberating and deciding government policy (as seems to be the case in the Swiss Federal Council, where the position of prime minister rotates and ministers enjoy considerable autonomy).

Both collectivity and collegiality were confused in the (primarily British) debate about prime ministerial versus cabinet government, which led to the inconclusiveness of that debate. Recently this debate has broadened into the hypothesis that most countries with parliamentary systems of government are witnessing a trend of “presidentialization.” Presidentialization occurs when prime ministers become less dependent on their political parties, fight more personalized election campaigns, and have more power over other ministers within the cabinet. This last aspect of presidentialization need not be the result of the prime minister being given more formal powers or resources; a greater need for coordination within the government, the internationalization of political decision making with the prime minister attending international summit meetings, and the tendency of the media to personalize government are also contributing factors to presidentialization. Others have criticized the ill-defined nature of the presidentialization thesis and have found little evidence for it.

Table 1 illustrates the poles of the two dimensions, on both of which intermediate positions can be discerned. Between collective and fragmented cabinets, for example, are segmented cabinets in which cabinet committees play an important role, especially where cabinet committees enjoy some degree of autonomy from the full cabinet. With regard to the distribution of power within cabinets, the intermediate position between monocratic and collegial cabinets takes hold when an inner cabinet dominates decision making. During 1970s and 1980s, for example, Canadian cabinets had both strong cabinet committees, which were even allocated their own budget at times, and an inner cabinet in the form of the Operations Committee of the Priority and Planning Committee. In Canada, an inner cabinet was set up because the cabinet itself had grown too large, but this need not be the only reason. Many coalition cabinets have an inner cabinet or coalition committee, bringing together the leaders of the governing parties to prevent intracoalition conflicts from threatening the survival of the government.

Table 2. Two Dimensions Of Cabinet Government

Cabinet Formation

By convention, a new cabinet is said to take office with each parliamentary or presidential election, with a change of party composition, or with a change of the head of government. Although the latter two changes can occur without elections, this is rare and usually intended as an interim solution after a cabinet crisis, to take care of government until the next scheduled or early elections are held. If the cabinet is monocratic, the president or the prime minister of a single party cabinet forms the cabinet without much interference from others. In practice, however, even such cabinets are often coalitions of sorts: prime ministers must unite their own party and appease rival factions by appointing rival-party leaders to cabinet positions; presidents in presidential systems often want to broaden support in the legislature to ease passage of their proposals by inviting politicians from outside their own party to join the cabinet.

Where cabinets are based on a coalition of parties, their formation usually involves intensive negotiations between party leaders. An extensive body of literature, primarily based on rational choice theory, seeks to explain the outcome of the formation process in terms of the cabinet’s party composition. Much less attention has been given to the allocation of particular portfolios to coalition parties. In 1996, Michael Laver and Kenneth Shepsle argued that the cabinet’s policies are determined by this portfolio allocation as each party sets the agenda for the government departments that are led by a minister from its own ranks, in fact assuming that all cabinets are both collegial and fragmented. Scholars who argue instead that collective decision making plays an important role in cabinets have recently drawn attention to the fact that, increasingly, the cabinet formation results in a written coalition agreement replacing the individual parties’ election manifestos as the basis for policy making; in the 1940s, 33 percent of European coalition cabinets had such a document, compared with 81 percent of such cabinets in the 1990s. In some cases the documents are quite comprehensive, with the record set by a coalition agreement of 43,550 words in Belgium (Müller and Strøm, 2008). Given the negotiations involved, the cabinet formation can take quite a long time. Forming monocratic cabinets and single-party cabinets takes less time, as does the formation of coalition cabinets with a fixed-party composition (the Swiss “magic formula”) or those based on a alternative combinations of parties may prolong the bargaining process and produce several failed attempts before a new cabinet can take office.

Bibliography:

- Andeweg, Rudy B. “On Studying Governments.” In Governing Europe, edited by J. Hayward and A. Menon, 39–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Andeweg, Rudy B., and Arco Timmermans. “Conflict Management in Coalition Government.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining, edited by Kaare Strøm,Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, 269–300. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Bagehot,Walter. The English Constitution, 1867. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1963.

- De Winter, Lieven, and Patrick Dumont. “Uncertainty and Complexity in Cabinet Formation.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining, edited by Kaare Strøm,Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, 123–157. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Helms, Ludger. Presidents, Prime Ministers, and Chancellors: Executive Leadership in Western Democracies. New York: Macmillan, 2005.

- Laver, Michael, and Kenneth A. Shepsle. Making and Breaking Governments: Cabinets and Legislatures in Parliamentary Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Müller,Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm. “Coalition Agreements and Cabinet Governance.” In Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining, edited by Kaare Strøm, Wolfgang C. Müller, and Torbjörn Bergman, 159–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Moe, Ronald C. The President’s Cabinet: Evolution, Alternatives, and Proposals for Change. New York: Novinka, 2004.

- Neto, Octavio Amorim. “The Presidential Calculus: Executive Policymaking and Cabinet Formation in the Americas.” Comparative Political Studies 39, no. 4 (2006): 415–440.

- Webb, Paul, and Thomas Poguntke. “The Presidentialization of Contemporary Democratic Politics: Evidence, Causes, and Consequences.” In The Presidentialization of Politics, edited by Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb, 336–356. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

See also:

- How to Write a Political Science Essay

- Political Science Essay Topics

- Political Science Essay Examples